From fish kill to world-record pursuit — the story of rebuilding

a trophy coppernose bluegill fishery from the bottom up.

In the world of trophy bluegill fishing, they're called slabs — coppernose bluegills so big they barely look real. On a quiet five-acre pond in northern Alabama, not far from Huntsville, pond owner Sarah Parvin was on the verge of growing one for the record books. Decades of careful management had transformed her pond into something remarkable: a dedicated coppernose bluegill fishery producing fish that turned heads across the industry. They called it the Slab Lab, and it was living up to the name.

Then, on a hot July morning, it started.

First one fish belly-up near the bank. Then another. Within hours, thousands of trophy coppernose bluegill were bobbing lifeless at the surface — years of careful management deteriorating in the Alabama heat. What had gone wrong?

What could have been the end of the story became the beginning of a new one. Natural Waterscapes partnered with Sarah and rallied multiple industry leaders to do something rarely attempted at this scale: a complete reset of both the water column and the sediment. Not a band-aid. Not a "wait and see." A deliberate, science-driven intervention to rebuild the Slab Lab from the bottom up. Today, the results are speaking for themselves: phosphate locked in the sediment, a food web showing robust signs of recovery, and a pond that's not just bouncing back but being rebuilt better than before.

This is that story.

The Slab Lab started roughly thirty years ago as a pond built from scratch by Sarah's father, Dennis Olive. Like many private ponds in the Southeast, it was originally managed for bass and bluegill — but Sarah pivoted the entire fishery toward a single, ambitious goal: growing world-record coppernose bluegill.

It was working. Years of selective harvest, precision feeding, and relentless daily management had produced fish that turned heads across the industry. Features in Mossy Oak Gamekeeper, Outdoor Life, ESPN, Barstool Outdoors, and Major League Fishing brought national attention. By late 2024, shock surveys were producing coppernose registering at 250%+ on the relative weight chart — 8-inch fish weighing what most 10-inchers weigh. The world record was in sight.

Then 2025 hit hard. Back-to-back winter storms froze the pond solid for eleven straight days — a worst-case scenario for a subtropical species. Fish losses, a supercharged algae bloom, and an emergency aeration response followed. The team stabilized and recovered, but the system was stressed and loaded with nutrients heading into summer. As Sarah put it: they knew they were flying too close to the sun, taking big risks for big rewards. This was the price.

Sarah Parvin with a trophy coppernose bluegill at the Slab Lab.

In July 2025, a regional heat dome settled over the South, pushing surface water temperatures past 92°F. The Slab Lab had been managed for years under a traditional "Green is Good" philosophy: heavy nutrient loads driving dense phytoplankton blooms, keeping visibility between 12 and 18 inches to maximize biomass production. The water looked productive. Underneath, the pond was a system on the brink.

The pond was thermally stratified, with an oxygen-rich surface layer floating on top of a completely anoxic deep layer loaded with toxic gases from decomposing organic muck. Then the weather turned. A heavy rainfall event dropped roughly four inches of cool, 55°F rain onto 92°F surface water, accompanied by sustained winds of 12 to 15 miles per hour. In shallow areas, that wind alone can disturb several inches of sediment. Combined with the thermal shock of cold rain hitting hot water, the stratified layers collapsed and mixed. In limnology, this is called a summer turnover, and in a pond this loaded, it's a death sentence.

As the team later described it: it was a perfect storm. Never just one thing, but several compounding factors all hitting at once.

When the anoxic bottom water mixed with the surface, the accumulated ammonia exerted a massive chemical oxygen demand. Converting just 1 mg/L of ammonia to nitrate requires approximately 4 mg/L of dissolved oxygen. The ammonia from the Slab Lab's bottom sucked the oxygen out of the entire water column. Fish that were already stressed from turbidity, pH swings, and the heat were pushed past the tipping point. As soon as that unionized ammonia spiked, they were done.

Dissolved oxygen at 0.07 mg/L. Effectively zero. The result was catastrophic. Trophy-class coppernose bluegill, years of genetics, selective harvest, and careful management, gone in a matter of hours. This wasn't a recreational pond that lost some bass. This was a nationally recognized fishery on the verge of producing a world-record fish.

When fish die and decompose in large numbers, they release enormous amounts of phosphorus and ammonia back into the water. Add that to the phosphorus already cycling out of the disturbed sediments, and the result is a nutrient bomb that can fuel toxic cyanobacteria blooms for years, even decades. The cyanobacteria was already there: Microcystis at the surface, Phormidium rising from the bottom in dark, leathery mats that people often mistake for string algae. Without intervention, the Slab Lab wasn't looking at a setback. It was looking at a cascading failure.

Sarah needed help. She made the call.

Thousands of coppernose bluegill lost in a single morning. July 2025.

The "Green is Good" approach to pond management is a traditional limnological axiom: high nutrient loads create dense phytoplankton blooms that shade out aquatic weeds and fuel the food chain from the bottom up. For decades, this was the standard for biomass production in aquaculture. And on the surface, it appeared to work. The problem was threefold. First, the dense blooms were dominated by cyanobacteria, which zooplankton can technically consume but derive almost no nutritional value from. Cyanobacteria lack the essential fatty acids, lipids, and sterols that zooplankton need to survive and reproduce, making them the nutritional equivalent of empty calories. Second, the heavy bloom was choking out sunlight to the bottom of the pond, smothering benthic habitat and preventing the growth of beneficial organisms in the sediment. Third, the excess nutrients that weren't being consumed were settling into the muck, building a massive phosphorus reserve that would continue to fuel blooms from below for years. All that apparent productivity was a biological dead end, and the system was building toward exactly the kind of catastrophic failure that hit in July.

When Natural Waterscapes got the call from Sarah, Heather didn't hesitate.

Before Heather even landed in Alabama, the team had already shipped RapidBac, a liquid nitrifying bacteria, because they knew ammonia levels would be dangerous after a fish kill of this magnitude. Sarah had already sent a water sample to the Natural Waterscapes lab in Pennsylvania. Regardless of what those numbers said, the team wanted product in the water as soon as possible.

The plan went far beyond cleanup. The goal was to take as much data as possible, as quickly as possible, so they could look at what went wrong and build a management plan to bring this fishery back. "We can just start reacting," Heather explained, "but let's learn from it. Because if we don't know all the factors that led this to where it's at today, then we know it's going to happen again."

Heather arrived with Hannah from Natural Waterscapes and went straight to the Slab Lab that evening. They grabbed dissolved oxygen readings at three different points around the pond, establishing multiple reference points rather than relying on a single measurement. They were back at dawn the next morning to collect the same readings again. The pond was running on fumes.

Then they did something most water testing misses entirely. Instead of just pulling surface samples, they lowered a deep water sampler to just above the sediment layer at the bottom of the pond. "Sometimes when you look at water quality from just surface samples, you can get a completely different picture of the health of a water body," Heather explained. "When we take samples from the deep, right at the interface with the organic muck, it can paint a completely different picture." In this case, the nutrient levels at the bottom were actually higher than at the surface.

Surface orthophosphate, the form of phosphorus that directly fuels algae growth, measured at 1.3 mg/L. For context, the target for a healthy fishery is below 0.05 mg/L. The Slab Lab was running at more than 26 times higher than optimal levels.

Cyanobacteria samples confirmed what they could already see and smell. The species identified were Microcystis, the colony-forming surface species that produces microcystin, Phormidium, a benthic species that grows on the bottom and rises to the surface in dark mats, and Planktothrix as well. Toxin samples were sent to GreenWater Laboratories in Florida and came back positive for all three categories: microcystin, anatoxin, and saxitoxin. Nobody was getting in that water without gloves.

Sarah was ready. "I have zero qualms about talking about how bad this water is," she said, "because we're going to fix it. And that's all that matters at the end of the day."

In the weeks following the July assessment, the data came back piece by piece, and each result confirmed that the Slab Lab's problems ran deeper than anyone could see from the surface.

The sediment phosphorus fractionation test revealed the full scope of the problem. This test quantifies how much reactive phosphorus is stored in the muck and how readily it can release back into the water. The results were staggering: approximately 20 pounds of reactive phosphorus per centimeter of depth in the top 10 centimeters of sediment. Total available phosphorus stored in the water column and benthic layer combined: over 1,000 pounds. Considering that just one pound of phosphorus can fuel 500 pounds of algae, this represented a massive and self-sustaining bloom engine that would keep firing indefinitely without intervention.

Under anoxic conditions, which were routine at the bottom of the Slab Lab due to stratification, that phosphorus becomes chemically soluble. It doesn't matter what you do at the surface. If the sediment keeps releasing nutrients from below, the cycle never breaks. This is internal loading, and it's the reason so many ponds with chronic algae problems never improve no matter how many treatments are applied.

With the data in hand, Natural Waterscapes built a comprehensive reset plan. The math was straightforward: at a known rate of 1.3 gallons of MetaFloc per pound of phosphorus removed, the team calculated a reset dose of 5 totes, approximately 1,375 gallons, of the biological phosphorus binder. They also planned applications of MuckBiotics to begin breaking down the organic sludge at the bottom, installation of new surface aerators to prevent the stratification that caused the original turnover, and deployment of a real-time water quality monitoring buoy to track conditions around the clock.

Jon worked behind the scenes coordinating equipment and logistics. The team assembled a crew that included Patrick, an aquatic biologist who specializes in invertebrate ecology and plankton analysis, and Chad, who would handle the heavy equipment work. Multiple industry partners were brought in to contribute expertise and resources. This wasn't going to be one company's effort. It was going to be a collaborative, data-driven reset of an entire ecosystem.

On September 30, 2025, the full team arrived in Alabama. The Reset was about to begin.

Standard water tests often miss the "legacy load" of nutrients trapped in pond sediments. That's why the team performed a sediment phosphorus fractionation, a test that quantifies how much reactive phosphorus is stored in the muck and how readily it can be released. Think of the sediment as a bank account that's been accumulating phosphorus deposits for years. Under the right conditions (low dissolved oxygen, warm temperatures, high pH) those deposits become soluble again, flooding the water column with algal fuel. This is internal loading, and it's the reason many ponds with chronic algae problems never improve no matter what surface treatments are applied. The phosphorus engine is running from below, and until you address it, the cycle never breaks.

The full team descended on the Slab Lab at the end of September. Heather led the operation. Patrick arrived with an Eckman dredge, plankton nets, and sampling equipment for a complete biological baseline. Chad was there to run the heavy equipment. Jon assembled and deployed a LakeTech monitoring buoy from the dock, giving the team 24/7 real-time data on dissolved oxygen and temperature at multiple depths from that point forward.

Patrick started with the sediment. The Eckman dredge is lowered to the bottom and triggered with a weight; it releases and grabs a sample from the top couple inches of the sediment surface. Unlike a core sample, which captures a vertical column, the dredge collects what's right at the interface where biology meets chemistry. Those samples would go back to the lab for invertebrate counts and community analysis, establishing a benchmark for the sediment recovery to come.

The cyanobacteria was still thriving. Phormidium was rising from the bottom in dark, almost black clumps that floated at the surface. "It's really common for people to think that's string algae," Heather pointed out. "But look at it. It's so much darker. If you see stuff like that in a pond, it's probably not algae. It's cyanobacteria. And that can actually be just as toxic as the stuff that makes this water green."

Meanwhile, Chad and Heather loaded the boat with six 30-pound bags of MuckBiotics and began broadcasting them across the entire pond. Unlike liquid bacteria that disperses everywhere, pellets have a concentrated area of influence, so getting even distribution throughout the water matters. Chad distributed the pellets while Heather drove the boat, working to cover all five acres as evenly as possible.

By the end of Day 1, the buoy was transmitting, the sediment samples were on ice, and the MuckBiotics were sinking into the sludge layer to begin their work. The team regrouped that evening to plan the main event: MetaFloc.

Day 2 was the main event. Five totes of MetaFloc, each holding 275 gallons, were staged and ready to go. The team ran a trash pump with suction lines dropped into the totes, pumping MetaFloc into the propeller wash of the boat and the surface aerators to get rapid, even distribution across all five acres. They moved fast. As Patrick explained: "Once we start going, we want to try to get as much of the product out as soon as possible so we can have good even spread coverage." Chad ran the pump. Sarah drove the boat. Jon directed positioning from the dock and drone.

MetaFloc is a biological phosphorus binder that works through dual mechanisms. Its flocculant gently binds suspended solids and dissolved phosphorus in the water column, forming heavy clumps that settle to the bottom. Unlike aluminum sulfate (alum), which aggressively crashes pH and can devastate zooplankton populations, MetaFloc creates a "soft" biological floc that binds nutrients without sterilizing the water or harming the organisms the pond needs to recover. Once settled, the beneficial bacterial cultures in MetaFloc continue working at the sediment surface, binding phosphorus in the muck and making it biologically unavailable. The settled material effectively "caps" the sediment, sealing the legacy phosphorus load beneath a biological barrier.

The results were visible within hours. Shades of green began to change, the fluorescent neon dimming to darker green, then mustard yellow, as the floc started binding the suspended particles and pulling them to the bottom. As Patrick put it: "It's not like algaecides where you're just kicking the can down the road or mowing the grass. This is changing the entire ecosystem for the better."

By the end of the day, the Slab Lab was visibly transformed. Sarah was seeing things she hadn't seen in years: rock piles, submerged habitat, even a feeder that had sunk years ago. Dennis stood on the dock and watched the water clear in real time. "With what Natural Waterscapes has brought to the table," he said, "their partnership with us has made all the difference in the world."

Aluminum sulfate (alum) is the traditional go-to for phosphorus removal in lakes, and it works, but at a cost. Alum treatments can crash water pH, which is devastating to zooplankton, the microscopic animals that form the critical link between algae and fish in the food web. In a pond where the entire goal is to rebuild that food web from the ground up, using a treatment that kills the organisms you're trying to cultivate is counterproductive. MetaFloc's biological approach achieves the same phosphorus binding without pH impacts, without water use restrictions, and with the added benefit of continued bacterial activity at the sediment surface, something chemical treatments simply cannot provide.

Heather was up early on Day 3, pulling surface and bottom water samples to compare against the readings taken before the MetaFloc application. Each test kit had to sit for 10 minutes before running. The team gathered around and waited.

Surface phosphate before the reset: 1.3 mg/L. This morning: 0.02 mg/L. A 98% reduction in 24 hours.

Bottom phosphate dropped from 0.16 to 0.05 mg/L, confirming that the MetaFloc had successfully settled through the water column and sealed the benthic layer. The sediment cap was holding. "The bottom sample is actually the more important one," Heather explained. "It tells us whether the sediment cap is doing its job. And it is."

Then came the visibility measurements.

The team measured 136 centimeters of clarity, just over 5 feet 4 inches. Heather turned to the camera with a grin: "I'm 5'4". So that's a great indicator." From 17 inches of pea soup to seeing the bottom of the pond. You could make out muck pellets on the bottom with floc settled on top of them, nearly burying them, less than 24 hours after the MetaFloc application.

But the moment that defined Day 3 wasn't in the test results. It was Sarah walking the banks of the Slab Lab that morning, seeing her pond for the first time with clear water. Seeing the bottom where her fish had lived, where they had spawned, where they had spent their days.

This is the moment that separates a real intervention from a cosmetic one. Plenty of products can make water look clear temporarily. The question is always what's happening beneath the surface. The lab data confirmed that MetaFloc wasn't just clearing the water. It was fundamentally changing the nutrient dynamics of the entire pond, from the surface to the sediment floor. And the woman who built this fishery could finally see it with her own eyes.

Before and after the MetaFloc application at the Slab Lab. 98% phosphorus reduction in 24 hours.

Orthophosphate (also called soluble reactive phosphorus, or SRP) is the form of phosphorus immediately available to algae. At 1.3 mg/L, the Slab Lab was running at more than 26 times higher than optimal levels for a healthy fishery. But the surface measurement alone doesn't tell the whole story. The bottom phosphate reading is equally important. A drop from 0.16 to 0.05 mg/L at the sediment-water interface means the MetaFloc successfully settled through the water column and formed a barrier over the legacy phosphorus stored in the muck. Without that cap, the 1,000+ pounds of phosphorus in the sediment would have continued cycling back into the water indefinitely, fueling bloom after bloom regardless of any surface treatment.

During the reset week, two Kasco 3-horsepower surface aerators were assembled and installed at strategic locations across the pond, positioned with drone guidance from above. Their job is straightforward but critical: force oxygen-rich surface water down through the water column to prevent the thermal stratification that caused the original fish kill. The LakeTech buoy confirmed the results immediately. Dissolved oxygen levels stabilized from top to bottom, day and night, eliminating the dangerous swings that had plagued the Slab Lab for years.

Six weeks post-reset, the team returned in November to conduct a full biological assessment. The question was no longer whether the water chemistry had improved. The question was whether the living systems were responding.

They were.

Patrick started with the benthic invertebrate community in the spawning areas, filtering sediment samples through a 500-micron sieve. Before the reset, the bottom was dominated by small oligochaete worms, pollution-tolerant indicators of low oxygen and high nutrient loads. Now the samples were full of chironomids (blood midges), and critically, the size class had increased dramatically. "That is so much bigger and better than what we had before," Patrick said, holding a specimen under the lens. "Before, there were no big ones. Zero. It was all really small worms. Now we're seeing this transition: bigger size classes, better composition." The target is 50 to 60 percent chironomids in the community, with mayflies and dragonflies expected to return as the sediment continues to recover over the coming seasons.

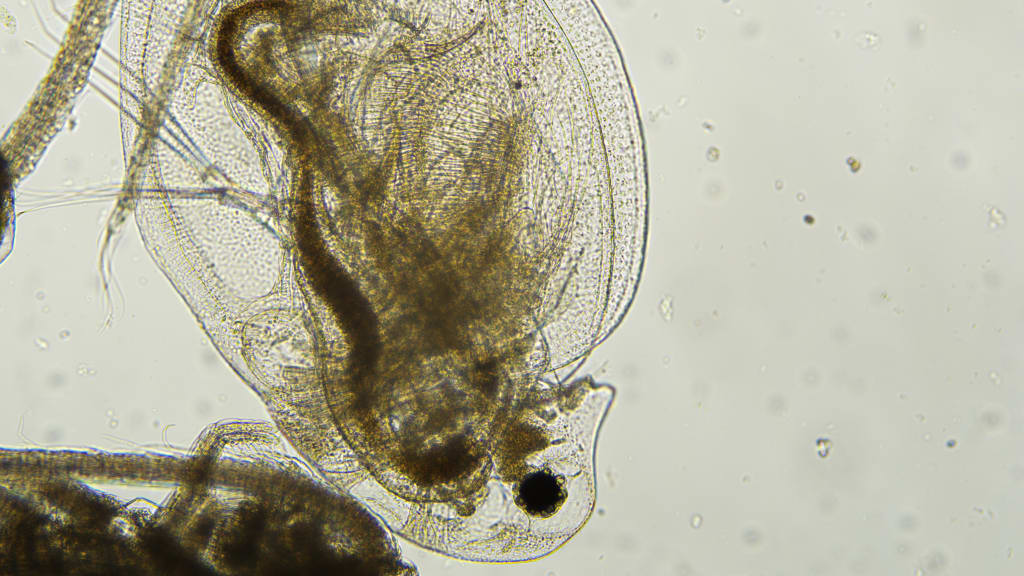

Then came the zooplankton. Patrick deployed a Wisconsin plankton net, an 80-micron mesh with a high-efficiency cone, towed vertically through the water column to capture 150 liters of composite sample. When the net came up, the team could see the zooplankton with the naked eye: clouds of Daphnia, Cladocerans, Copepods, and Bosmids, all large-bodied, all rich in lipids and essential fatty acids.

"I can tell you right now we're well above our thresholds," Patrick said, holding up the concentrated sample jar. "That is only 150 liters. Look at that." The sample looked like milk, thick and alive. Sarah took one look and the moment hit her. "Are you getting emotional over zooplankton?" someone asked. "Yeah," she said. "It's your babies."

And the phytoplankton told the most dramatic story of all. Lab analysis of cell counts showed the transformation in hard numbers: the pond had started at over a million cells per milliliter, with cyanobacteria comprising 53% of the total community. Six weeks post-reset: 4,500 total cells per milliliter. Cyanobacteria: zero. The entire community had shifted to beneficial green algae and diatoms, species rich in the essential fatty acids that zooplankton need and that ultimately grow trophy fish. As Patrick put it: "Eating cyanobacteria is so nutritionally poor. It's like the iceberg lettuce of the pond world. Now we've got the good stuff."

The difference between a cyanobacteria-dominated pond and a diatom-dominated pond isn't cosmetic. It's the difference between a food web that works and one that doesn't. Cyanobacteria lack the essential fatty acids (PUFAs) and sterols that zooplankton need to survive and reproduce. While zooplankton can technically consume some cyanobacteria, the nutritional value is negligible, and large colonies of Microcystis are also physically too large for most zooplankton to ingest. The result is a biological dead end: energy from the sun gets trapped in toxic scum, dies, sinks, becomes muck, releases more nutrients, and starts the cycle over. Meanwhile, the dense bloom blocks sunlight from reaching the bottom, smothering benthic habitat and suppressing the invertebrate community that fish depend on.

Diatoms and green algae, by contrast, are the right size, the right nutrition, and the right energy package. When they dominate the phytoplankton community, zooplankton thrive, and that energy flows efficiently up to the fish. The shift from over a million cells per milliliter with 53% cyanobacteria to 4,500 total cells with zero cyanobacteria is the single most important indicator that this ecosystem is now functioning as it should.

The long-term goal for the benthic community is the return of sensitive indicator species like mayflies (Ephemeroptera) and dragonflies (Odonata), which require clean sediment and stable oxygen levels. Their presence would confirm that the sediment recovery is complete, a process that typically takes one to two full seasons.

Daphnia at 10x magnification from the Slab Lab. The return of zooplankton confirms the food web is firing. Image by Natural Waterscapes.

The monitoring continues. The LakeTech buoy tracks dissolved oxygen around the clock, and the team watches the spread between daytime highs and nighttime lows. A widening gap signals an algae bloom building momentum, and a maintenance dose of MetaFloc brings it back into range before it becomes a problem. Each water sample, each microscopy session, each data point from the buoy adds another chapter to a story that is still being written.

The Slab Lab's reset is progressing. The water quality has been stabilized. The sediment has been capped. The food web is firing. And there's already proof that life is coming back: the team has found brand new year-of-young fish in the shallows, hanging out in the habitat near the banks, right where they should be.

The management philosophy has fundamentally changed. The Slab Lab is no longer managed for "color." It's managed for constituents. Every decision is driven by data: what's in the water, what's in the sediment, what's growing in the phytoplankton community, and what's eating it. The target is precision, maintaining soluble reactive phosphorus below 100 micrograms per liter to support diatom and green algae growth without giving cyanobacteria a foothold. When phosphorus levels creep up from fish feeding inputs, maintenance doses of MetaFloc bring them back into range.

The two Kasco surface aerators now prevent the thermal stratification that caused the original turnover. By forcing oxygen-rich surface water down to the bottom, the aerators keep the sediment-water interface oxygenated, and oxygenated sediment chemically locks phosphorus in place, providing a second line of defense beyond the MetaFloc cap. The LakeTech buoy watches it all in real time, ensuring dissolved oxygen never drops below the thresholds the team has set.

As Sarah put it from the beginning: "Awareness precedes change. We've got to know what we're dealing with." Now they do. And they're collecting every data point along the way, not just for the Slab Lab, but so that it can be used for years to come by anyone managing a pond or fishery.

The comeback is underway. Sarah Parvin with a coppernose bluegill at the Slab Lab.

The goal hasn't changed. A world-record coppernose bluegill, grown in a five-acre pond in northern Alabama. It's going to take time, likely the better part of a year or more. But every indicator suggests the Slab Lab isn't just recovering. It's being rebuilt better than it has ever been. And the team that rallied around this pond isn't going anywhere.

Follow along as new chapters are added. This page will be updated regularly as the Slab Lab continues its journey from reset to record.

New chapters are added regularly as the recovery continues. Subscribe to our YouTube channel and follow along as the Slab Lab makes its way back to world-record territory.